Crossing the line

Findings from a study of online abuse of England footballers

Note: This post references the racist abuse of individuals on social media. No explicit examples of such abuse are included.

England play Italy in Naples tonight in a repeat of the final of Euro 2020 - an encounter Italy edged on penalties, after agonising misses from Jadon Sancho, Bukayo Saka, and Marcus Rashford. Regretfully, the match is best remembered for events that took place in its aftermath, with the three England players receiving a torrent of racist abuse on social media.

My experience of these events was perhaps uniquely weird. At the time, I happened to be collecting data from Twitter for my master’s thesis investigating abuse of footballers on social media. My initial despair at England’s agonising loss gave way to a sort-of perverse giddiness as I saw the news unfolding. I whipped my laptop out, first anxious about whether my hacked-together data collection script would be able to cope with the volume of tweets (it did, well done me and the Twitter engineering teams), and second intrigued to see how the reaction was unfolding on social media.

I grepped log files knowing what I was going to find, but I really wasn’t at all prepared for the grim reality of seeing this real-time stream of the most shocking and abhorrent abuse, some of it horrifically racist, being aimed at the England players. This was of course widely reported in the media at the time.1

Following the match, I found myself in this privileged position of being one of the only people in the world outside of Twitter who had instant direct access to a database of tweets aimed at all the England players involved in the game that night. The analysis of this data and the events surrounding it become a core component of my thesis, enabling me to conduct a systematic quantitative study to better understand the scale and severity of the issue.

Unfortunately, life got in the way of me finding the time to write anything in public about my findings. However, come the start of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, I started my data collection script running again and repeated the analysis for England’s World Cup matches. And now I have, finally, got around to writing this blog detailing what I learned from my analysis of the two tournaments.

In the remainder of this blog, I’ll briefly describe the methodology I used (I’m planning to write a more detailed blog on this - there were lots of challenges and tradeoffs that may be of broader interest for online harms research), and detail the findings. I hope you find it interesting, and I’d love to hear any thoughts you might have on this.

Methodology

I chose to use Twitter as the data source since it is the main platform on which the online public conversation about football takes place, the majority of the England players have a presence there, and it has a user-friendly API for data collection which, at the time2, was free to use.

The methodology can be broken down into three distinct stages: data collection, classification of hateful tweets, and analysis.

Data collection

I collected tweets from Twitter using its Filtered Stream API. This API allows you to connect to a data stream and consume all tweets that match a filter you specify. For example, a simple filter could be set to collect all English language tweets containing the hashtag #ItsComingHome as follows:

"value": "#ItsComingHome lang:en"For my project, I first identified the Twitter profiles of each member of the England squad, and then setup filter rules to collect all tweets that either mentioned their Twitter handle, or were replies to tweets they had posted. The filter rules for this selection can be seen on GitHub here.

Note that this approach does not capture the whole conversation, since there will be tweets about the players that do not directly reference their Twitter handle, but may instead use the players’ names, or not explicitly refer to them at all. However, specifying more complex rules that aim to capture these additional parts of the conversation would be very challenging, could never be perfect, and could bias the data collection in favour or against certain players. Of more immediate practical importance to me at the time was the fact that Twitter set limits on the number of tweets a single client could consume from the API. Collecting just replies and mentions alone enabled a “fair” analysis, since tweets were collected for each player in the same way, and also meant I stayed *just* shy of Twitter’s data collection limits. The numbers reported here may therefore be considered a ‘lower bound’ for the actual volume of abuse levelled at players on social media.

Here’s a summary of the data collection:

Euro 2020

Data collection period: 19th June - 17th July 2021

Games covered:

- England vs Germany (Round of 16)

- England vs Ukraine (Quarter-final)

- England vs Denmark (Semi-Final)

- England vs Italy (Final)

Number of tweets collected: 823,474World Cup 2022

Data collection period: 28th November - 16th December 2022

Games covered:

- England vs Wales (Group stage)

- England vs Senegal (Round of 16)

- England vs France (Quarter-Final)

Number of tweets collected: 190,639Classification of hateful tweets

Once tweets were collected, the Perspective API was used to classify tweets as hateful or otherwise. Perspective is a best-in-class, publicly available machine learning model for detecting online hate speech.3

Data analysis

I carried out a zero-inflated negative binomial regression in a bid to work out a relationship between variables such as the player’s ethnicity, domestic club, penalty outcomes, etc. with the number of hateful messages they received. This looked (and sounded) impressive, but was somewhat convoluted, and ultimately not that appropriate or helpful for a dataset that covered only a small number of matches.

In the end, the most interesting and compelling findings came from two simpler techniques: counting things and plotting things. Some of the findings from my counting and plotting are discussed next.

Findings

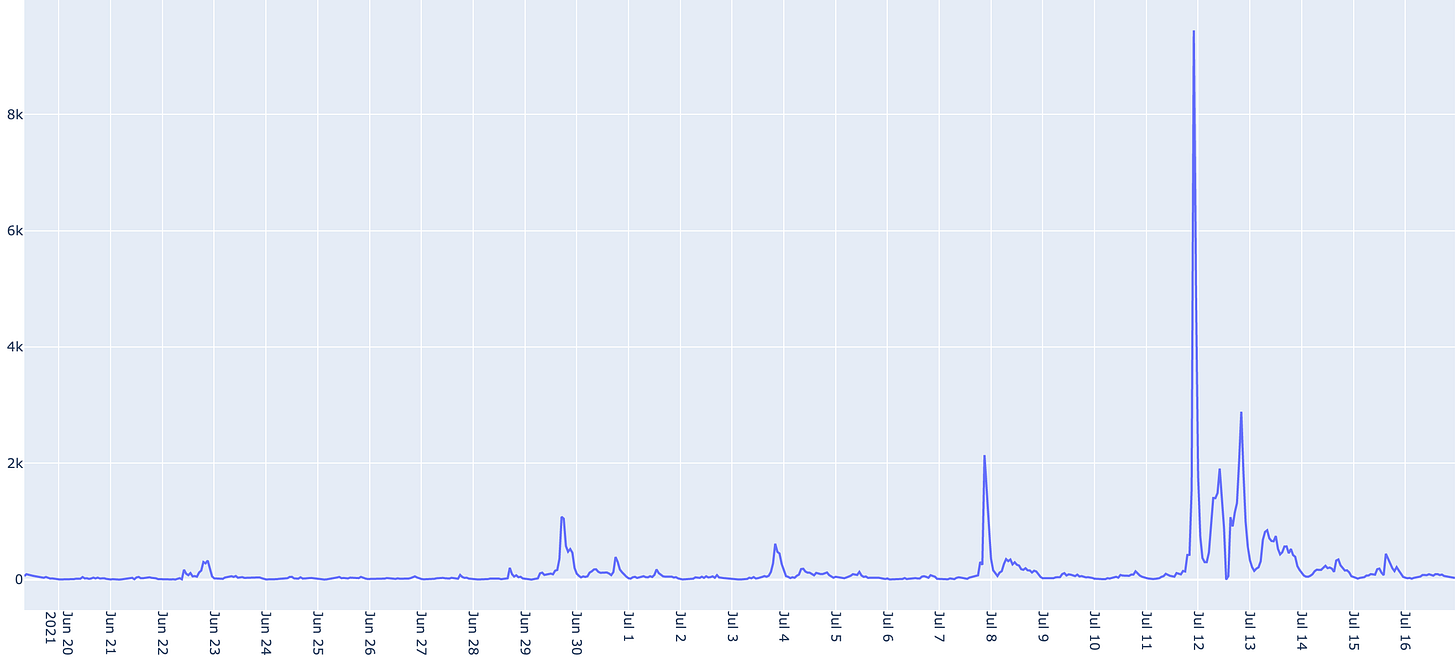

1. England’s tournament exits were major flashpoints for abuse

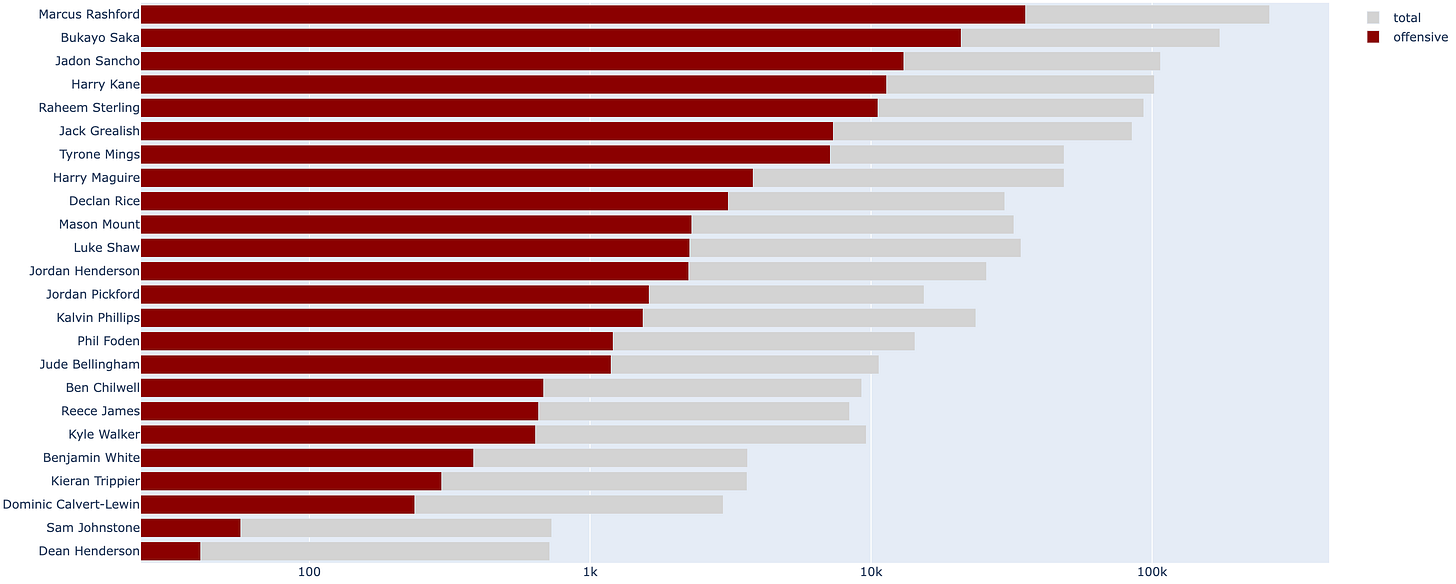

In both tournaments, the overwhelming majority of abusive tweets came in the aftermath of England’s last game of the tournament - their final loss on penalties to Italy in the Euros, and their quarter-final exit to France at the World Cup. The plots below shows the number of hateful tweets across the data collection period for both tournaments, with significant upticks following these games.

(High-res are figures available for the Euros and the World Cup)

This is unsurprising: frustrated fans, angry after a disappointing result take to social media to vent at the players they regard as responsible.

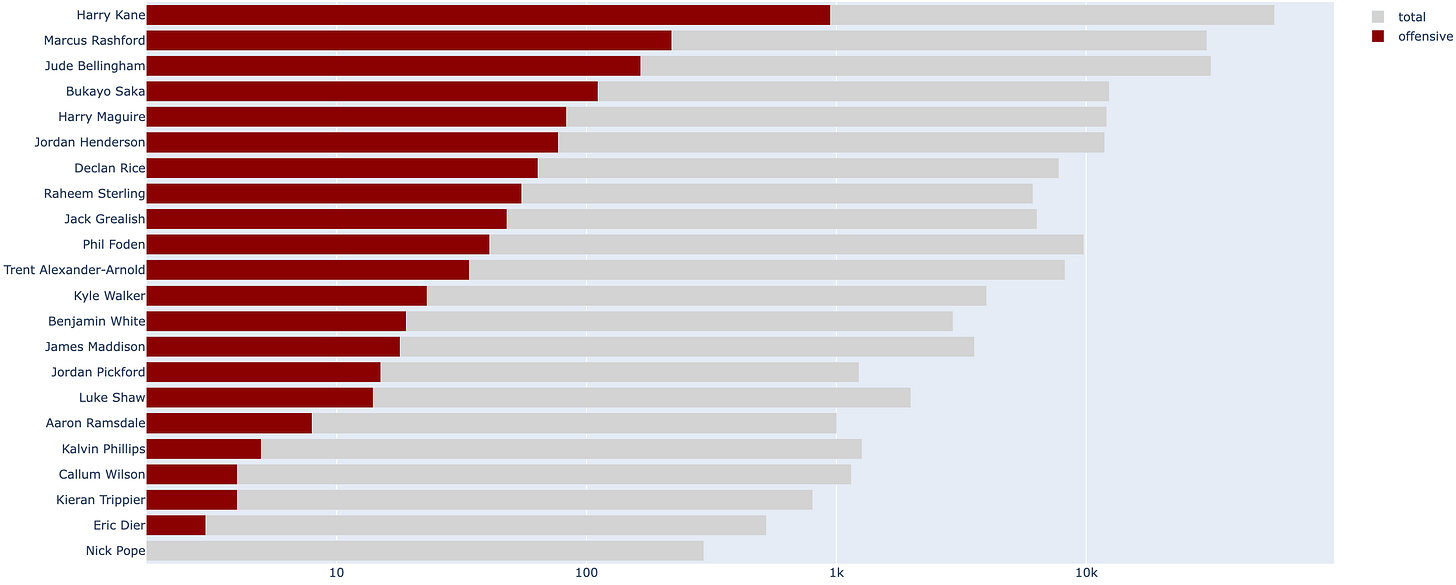

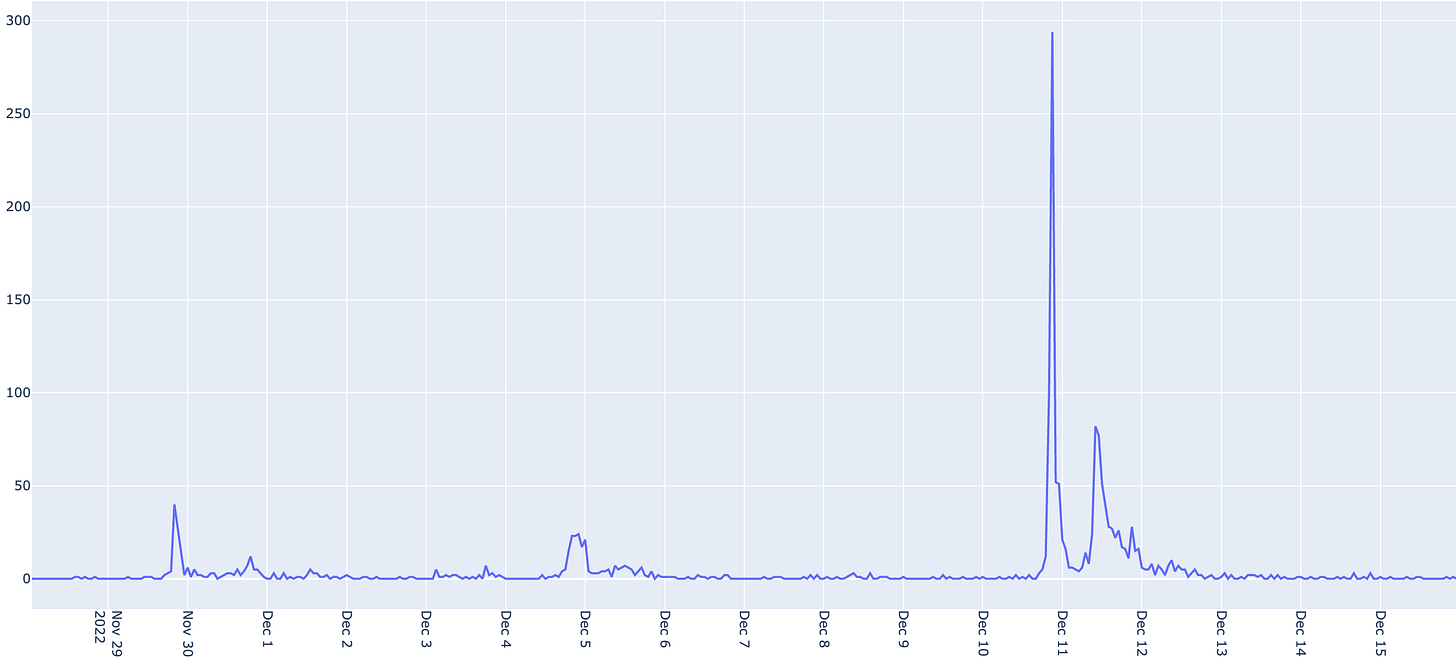

2. The overwhelming majority of hateful tweets were directed at a small number of players

In both tournaments, a small number of players were the target of the majority of abuse. Here's the 10 most-targeted players during the Euros:

Marcus Rashford: 36036 hateful tweets

Bukayo Saka: 21466 hateful tweets

Jadon Sancho: 13249 hateful tweets

Harry Kane: 12041 hateful tweets

Raheem Sterling: 10836 hateful tweets

Jack Grealish: 7824 hateful tweets

Tyrone Mings: 7298 hateful tweets

Harry Maguire: 3849 hateful tweets

Declan Rice: 3206 hateful tweets

Mason Mount: 2413 hateful tweets

These are plotted relative to the total number of tweets received by each player below (note the log scale on the x-axis: only a small percentage of tweets were hateful, so a log scale is used to make these discernible). High-res available here.

And during the World Cup:

Harry Kane: 947 hateful tweets

Marcus Rashford: 219 hateful tweets

Jude Bellingham: 165 hateful tweets

Bukayo Saka: 111 hateful tweets

Harry Maguire: 83 hateful tweets

Jordan Henderson: 77 hateful tweets

Declan Rice: 64 hateful tweets

Raheem Sterling: 55 hateful tweets

Jack Grealish: 48 hateful tweets

Phil Foden: 41 hateful tweets

Again, plotting relative to the total number of tweets (high-res here):

As can be seen, Marcus Rashford, Bukayo Saka, and Jadon Sancho were targeted most in the Euros, and Harry Kane at the World Cup. In fact, the abuse aimed at Rashford, Saka, and Sancho at the Euros accounts for 77% of all of the hateful messages received by England players during the data collection period. And those directed at Kane at the World Cup account for 48% of the total. That these players were targeted is again unsurprising: all 4 missed crucial penalties that led directly to England’s defeat and elimination. Whilst they may have been consoled by their teammates and supporters in the stadium, others were quick to vent their anger online.4

This finding concurs with research carried out by the PFA in 2020 into online abuse during the Premier League season, which found that Raheem Sterling, Wilfried Zaha, and Adebayo Akinfenwa received over 50% of all hateful messages. This pattern has also been seen outside of sport, with a 2016 study by the Anti-Defamation League finding that in a study of 800 Jewish journalists, 10 received over 83% of the antisemitic abuse observed. Furthermore, tweets by the players in the days following the match provoked further waves of hateful messages, a pattern also previously observed in these two studies.

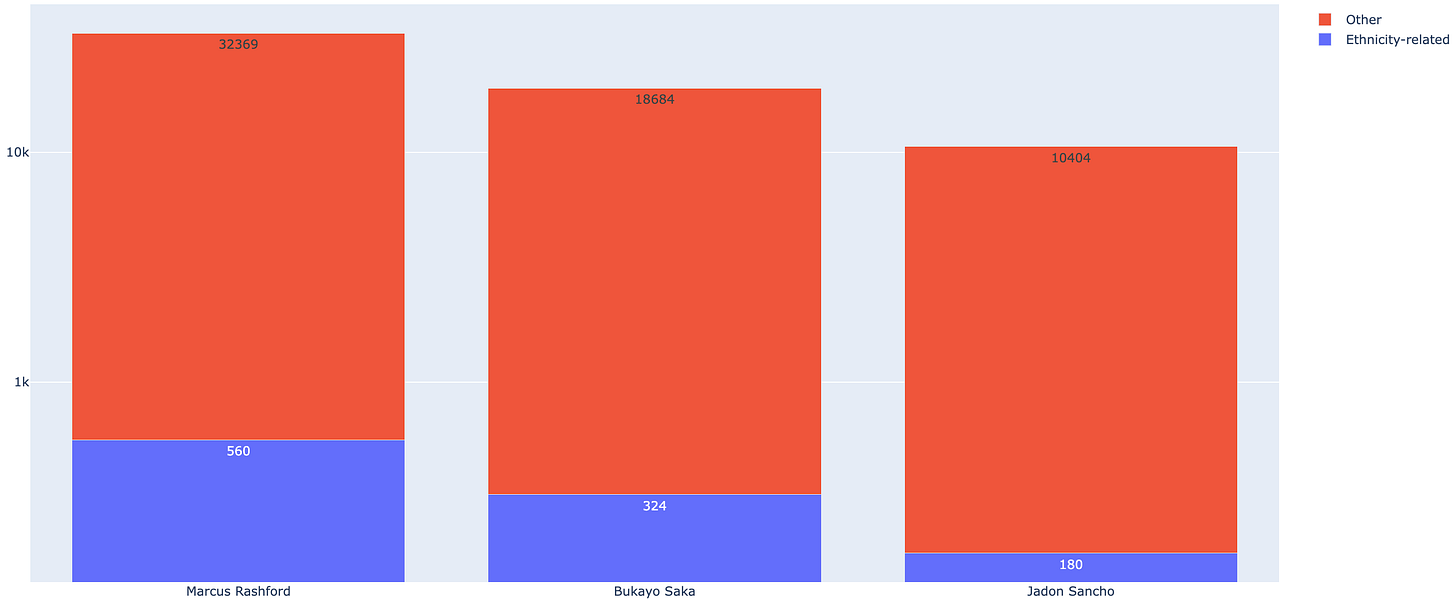

3. Rashford, Saka, and Sancho were targeted with racist abuse

Perhaps the most unsurprising finding! It is well established that these players were racially abused on social media, with many examples showcased during the heightened media attention that followed the final. Using the data I collected, I was able to get a handle on the scale of this. This plot shows the proportion of hateful tweets aimed at the three players that were related to ethnicity (high-res here):

Again, note the log plot - it is only a relatively small percentage of the tweets that are related to ethnicity. This is not to say that the impact of these tweets is small however. Being on the receiving end of potentially ~500 explicitly racist tweets in the space of a few days (likely in addition to similar hate sent via DM and other means) is undoubtedly a horrifying and potentially traumatic experience. Though not reproduced here, I can attest to the abhorrent nature of some of these tweets having viewed them myself. Just receiving one such message would be a horrendous ordeal.

Also of interest is that a number of tweets used emojis to express racist hate, with a manual review of 889 tweets containing monkey or banana emojis identifying 84 of them as being hateful. The Perspective API failed to flag these tweets as hateful, pointing to a ‘blind-spot’ in these AI models for emoji-based hate. Recent work has helped to plug this gap, and I suspect models would do a much better job of identifying this type of hateful content today than they did when I was carrying out this work in Summer 2021.

4. The scale of abuse was significantly larger at the Euros

The scale of abuse following the Euros final defeat was ~100 times greater than after the World Cup exit. There are a number of contributing factors that could be at play here:

The Euros final was in many senses a ‘bigger deal’, as this was the first time the England men’s team had reached the final of a major tournament since 1966, and it was taking place on home soil. The increased jeopardy may have led to a more intense response to the defeat.

Twitter’s policies and monitoring may have improved between the two tournaments. Given the high-profile nature of the abuse following the Euros, it is highly plausible that Twitter took significant steps to prevent a repeat during the World Cup.

Changes in the Perspective API. The classification of tweets as hateful or not hateful for the two respective tournaments was carried out approximately 18 months apart. Whilst the same thresholds were used to classify a tweet as hateful or not in both cases, it is possible that updates to Perspective in that 18 month period could create discrepancies. For purposes of backwards compatibility, one would hope any changes would not have led to too significant a difference, but ideally I would have evaluated both datasets using the same version of the Perspective API.

Racist attitudes exacerbated the level of abuse in the Euros, which was focused on the penalty misses of 3 non-white players, compared to the World Cup, which was focused on a miss by a single white player.

The abuse of Saka, Rashford, and Sancho became a major national and international news story, and this widespread coverage encouraged greater conversation on Twitter, a percentage of which would have been additional abuse aimed at these players.

We don’t have the data to establish causal links here, but it is likely that some combination of the above contributed towards the higher level of online hate observed during the Euros.

Conclusion

Online hate against footballers has been well-documented in recent years, and here I’ve tried to lay out some empirical findings from probably the most high-profile incident there has been. I hope by sharing this work I can contribute in some small way to the ongoing efforts to tackle online hate.

I hope to find time to write in more detail about some of the topics discussed here, but in the meantime do reach out with any thoughts you might have.

I’m not up to speed on this, but it seems like API access has been somewhat restricted as one of many recent sweeping changes at Twitter

At the time of writing, the free version of Perspective is rate-limited to 1 request per second. For the Euros, with over 800,000 tweets to classify, it took almost 2 weeks to classify all the tweets.

For an interesting read on how social media can lead people to dish out abuse they would not dream of saying in person, see the Online Disinhibition Effect.